The Trek Negative

& Scene

29D

by Dave Tilotta

Welcome back to the Articles Page of startrekhistory.com. We hope you

enjoyed our previous piece because we’ve readied another for you.

But, contrary to what we said at the end of that last article, we’re

going to take a bit of a diversion and discuss something different: negative

film. We hope you don’t mind the course change, but if you bear

with us, you’ll get to see something special at the end: never-before-seen

film footage of an unused take from Whom

Gods Destroy - restored from an original camera negative!

But I get ahead of myself…

We promise that the article on the journey of the film clip from studio

to collector is coming, and when it arrives it will be a fascinating trek

through clip history. But this opportunity - the Trek negative - literally

came knocking on our door, and to quote John Lennon, "Life is what

happens to you while you're busy making other plans." Enjoy!

|

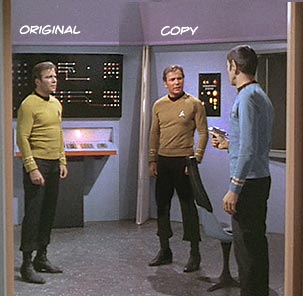

| Garth as a photocopy. |

Film clips from Star Trek negatives are rare for a couple of reasons. First, the negatives were (and still are) highly protected by the studio because they were the original source material and essentially irreplaceable. If you recall from our previous discussion, the studio generally produced internegatives to serve as safe substitutes. Thus, Desilu/Paramount simply didn’t release much negative film to Lincoln Enterprises or anyone else for distribution to the fans.

Secondly, negative film clips were not of much interest to the collectors in the 1960s-1970s. Simply, the clips were not really viewable with a home 35mm slide projector. After all, they were negative and would look pretty bizarre and meaningless projected on a wall. Of course, any camera shop back then could have printed them to make a positive, but why would anyone have bothered? Positive film clips were readily available at the time that were just as interesting, unique and fade free.

However, negative film clips are still desirable, especially today, because they yield the sharpest images and highest color fidelities in comparison to images made from positive clips, all other things being equal. This is because the original negatives came straight from the motion picture camera and did not go through any copying process (e.g., via a contact or optical printer) that degraded their images. Thus, they are as clear and as focused as they possibly can be. Also, and as discussed later, the original camera negatives (OCNs) have not faded to the same extent as the positive prints.

Anyone who’s watched the re-mastered Star Trek episodes should

be able to attest to the benefits of using OCNs. One of the major reasons

that the re-mastered Trek episodes are so pristine and vibrant is that

the live action components have been digitally transferred directly from

the negatives. In contrast, the quality of the episodes currently available

on DVD is due to the fact that those transfers were performed from prints

a generation or two removed from the original negatives and/or internegatives.

(A possible exception to this is Shore Leave

that appears to have been transferred directly from an internegative

or interpositive.) The process of creating a print is analog, and

to use the analogy of a photocopier, each copy of a copy compromises clarity,

color and contrast, albeit subtly, during the film duplicating process.

To be fair though, the 35mm prints used in the current DVD's, combined

with the fine eye of the colorists, are far superior to the original syndicated

Star Trek episodes seen on televisions during the 1970's on 16mm prints.

Negative Film and Fading

In this article, we show images from Whom Gods Destroy scanned from Eastman

Kodak type 5254

negative film. This stock was first introduced in 1968 and was considered

to be a great improvement over previous stocks because it was a faster

film. By “faster,” we mean more sensitive to light, so that

the studio light levels could be reduced significantly when shooting with

this film over some of the other stocks. Unfortunately, like the Eastman

Kodak positive color film, the Eastman Kodak 5254 negative film also fades

over time.

| The picture on the right shows a scan of a negative film clip. It’s obviously a negative because 1). the image is reversed and 2). the image exhibits an overall orange hue. For those interested, the orange hue is from a mask in the film used to optically correct for the imperfections in the color dyes. For those not interested, please skip over the previous sentence. |  |

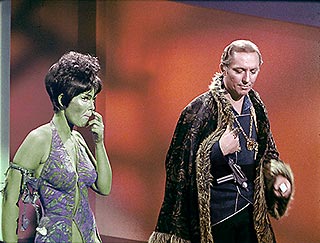

| When a print is made from the film, or the digital image inverted using software, a positive is generated and the orange mask removed. The picture on the right shows the inversion of the negative image from above. Note the depth and width of the color palette used in Star Trek. |  |

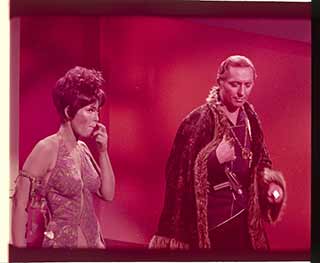

| But has the negative faded? As said previously, the 5254 negative film does fade over time. However, based on our experience (and some assumptions on the storage environments of the clips), the degree of fading appears to be less than that of the positive film. For example, the picture on the right shows an un-restored scan from an Eastman Kodak color positive film clip from the same episode. Note the characteristic magenta color that indicates fading. |  |

| When the above image is restored, the picture on the right is obtained. Notice that the hues and saturations of the colors in the restored image are similar to those of the inverted and color corrected negative image shown above. However, what is not apparent is that the color information in the scan of the positive image had to be manipulated to a greater extent. It’s true, and you’ll just have to trust us on this. |  |

Rolls of Film

Excluding network broadcast copies, uncut rolls of original

35mm positive film from Star Trek are rare. And needless to say, uncut

negative rolls are exceeding rare. Unfortunately, most of the rolls and

strips that were unused by the production team ended up either in the

trash bin or carved into individual frames. So today, whenever a roll

of any substantial length appears, it is historically priceless and certainly

worthwhile to keep intact.

Consequently, we were delighted when we were contacted by Mr. Lee Gately and informed that he possessed a small roll of negative film that had belonged to his late uncle Mr. Carl Shoen. Carl was a property man in Hollywood who worked on Star Trek and also worked on several movies including the original Willard starring Ernest Borgnine. This negative roll has been in Lee’s family since it was acquired back in 1968, and Lee generously loaned it to us so that we could share it on startrekhistory.com.

But what do you do with a 35mm roll or strip when you want to view the

motion picture? Unfortunately, unlike 8mm or even 16mm film, many people

do not possess the equipment at home to project the 35mm format. This

is probably for the best because old film can be brittle and spliced,

so the process of running it through a projector may permanently damage

it. The best and safest way to view old film is have it transferred to

a digital format. Once transferred, it can then be recorded onto a DVD

so that it can be viewed on a home player or computer. This is what we’ve

done to the negative roll, and the process is described below.

|

| Telecine

(phonetic pronunciation: "tel-e-Sin-ee" or "tel-e-Sin-a")

n. Machine or process used for transferring motion picture film into

electronic form. Colorist (phonetic pronunciation: “Col-or-ist”) n. 1. Person who operates a telecine and its associated equipment. |

I have to admit that I jumped at the chance to observe the telecine of this roll because I was intensely curious as to the nature of the scene that had lay hidden for nearly 40 years. So, I tucked the film under my arm and drove to the “studio” one morning with three cups of coffee and palpable anticipation under my belt (figuratively speaking). Upon arriving there, I accompanied the colorist to the back of a tiny room filled with wires, computers, and film projectors to find a telecine sitting there as big as a soda machine. Seriously, the telecine resembled an old computer bank from 1967 Earth as depicted in the episode Tomorrow is Yesterday.

Before loading the film into the apparatus, the colorist first affixed the ends of the film to leaders using special adhesive tape. I asked him why he didn’t more firmly splice the leaders on as I did as a kid when I made my home movie Gorgo: The Zombie Terrier From Space. The colorist explained that the modern telecines don’t actually use the sprockets of the film to move it so there is no reason to splice the leaders using cement. He went on to say that sprocket-less transfers were better anyway because many older films, in particular, have distorted and/or damaged sprocket holes. By avoiding the sprocket perforations, he said, you get a much more stable transfer with less risk of damage to the film.

|

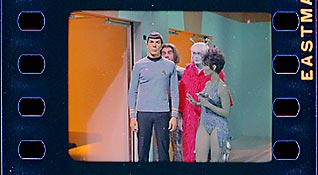

| Roll of negative film showing a portion of scene 29D from Whom Gods Destroy, courtesy of Mr. Lee Gately. |

After fiddling with the color a bit using joysticks located on the telecine control panel, the colorist pushed a button and streamed the digitized video to his computer and onto a DVD. After one minute, it was done: A digitized movie of the original negative, Whom Gods Destroy, Scene 29D!

As you are about to see, the bulk of the film shows an unused dolly in shot of Leonard Nimoy reacting to the conversation between William Shatner (Kirk) and Steve Ihnat (Garth). The scene occurs towards the beginning of the episode, and this particular footage was filmed as part of its coverage. The shots are used to cut in with the master shot, which is usually a wide shot. We speculate that the editor chose not to use this reaction shot because the bulk of the scene is focused on Kirk and Garth. Also, there is a slight scratch on the right side of the shot that runs through out. Although this might have ruled out the footage from being usable, it in no way deters from the historical significance of the film. The end of the footage shows a person, most likely the assistant cameraman, checking the lens of the camera for dust and lens flares.

We should point out that we’ve further color corrected

the movie to adjust for 40 years of fading. Unlike the OCNs from the series,

which are stored in a precisely

controlled environment, this roll was stored in a garage under less

than ideal circumstances. So, some chemical alteration and physical damage

was to be expected. Nevertheless, the degree of fading and damage was

minimal relative to rolls of positive film we’ve encountered stored

under similar conditions. Also, the colorist had no DVD to compare the

footage with and made his own assumption on exposure.

Presented below is the original color inverted and corrected footage along

with some variations created by our video editor Landru.

Click on any of the listings to the left of the slate to play that particular

movie. Please note that there is no original sound for this short clip.

Sound was recorded separately and is not available with this roll. Also,

note that Yvonne Craig (Marta, the Orion woman) gives Richard Geary (the

Andorian) the phaser pistol. This action is not seen in the episode and

thus gives the impression of a continuity error. Specifically, the broadcast

version first shows Marta with the phaser, and then later in the episode

in a wide shot we see the Andorian with the phaser.